Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav Kolkata event honours four Clergymen

Pope Francis asks businesses to support working women: They’re ‘afraid to get pregnant’

Study: Christianity may lose majority, plurality status in U.S. by 2070

Indian politician declines Magsaysay Award under party pressure

Like John Paul II, Pope Francis heads to Kazakhstan during time of war

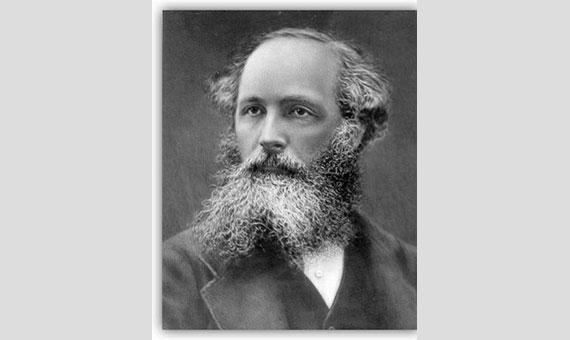

James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879) is a great British scientist who dominated the intellectual landscape of the science of electricity. His contributions are in the fields of optics, and electromagnetism. He developed the theory of electromagnetism and the chemical kinetic theory of gases. Maxwell’s equations of electromagnetism led to the prediction on the existence of electromagnetic waves which was discovered by Heinrich Hertz.

During his undergraduate studies he fell ill for a month and he was nursed by an evangelical pastor. This experience is said to be a kind of conversion for him though he had been a regular participant in the Church services. His friend recollects that “at this time his religious views were greatly deepened and strengthened.” His letter from Cambridge to the pastor speaks of his new religious blend of mind: “I maintain that all the evil influences that I can trace have been internal and not external, you know what I mean — that I have the capacity of being more wicked than any example that man could set me, and that if I escape, it is only by God’s grace helping me to get rid of myself, partially in science, more completely in society, — but not perfectly except by committing myself to God.” Here he makes the radical comment that he regards science as part of God’s plan for human salvation.

He became a member of the Cambridge Apostles which was a debating society of the elite, and this was crucial in refining his religious development. He upheld the independence of scientific and religious truth. In the meantime, he held that “scientific conclusions could enrich religious contemplation of God’s actions in nature.” Maxwell refused to accept any uncritical juxtapositioning of science and religion. He said that the use of partial scientific knowledge to interpret Bible can be harmful. Ian Hutchison comments of Maxwell: “He has no need of scientific proofs of Christianity. Instead, his expressed concern is that ill-judged linking of specific scientific theories with religion will be an impediment to the growth of science. His emphasis, in relating science and faith, is on science’s enhancement of our wonder at the glory of creation.”

He even dared a religiously motivated interpretation for the uniform and eternal nature of atoms. He wrote in a letter in 1879 regarding membership in Victorian Institute: “I think of men of science as well as other men need to learn from Christ, and I think Christians whose minds are scientific are bound to study science that their view of the glory of God may be as extensive as their being capable of.”

Leave a Comment