Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav Kolkata event honours four Clergymen

Pope Francis asks businesses to support working women: They’re ‘afraid to get pregnant’

Study: Christianity may lose majority, plurality status in U.S. by 2070

Indian politician declines Magsaysay Award under party pressure

Like John Paul II, Pope Francis heads to Kazakhstan during time of war

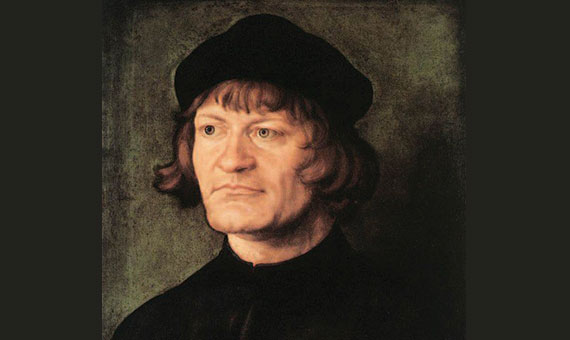

Huldrych Zwingli (also Huldreich or Ulrich) was a Swiss Reformer and Humanist, who laid the foundation for the Reformer Tradition of Protestantism. Together with Luther, he was one of the two leading protagonists of the early Protestant movement which had independent roots although the insights often paralleled. He denied all dependence on Luther and said: “I did not learn my doctrine from Luther, but from God’s Word itself.” Thus, although potential allies in their struggle against Rome, they clashed over the understanding of the Lord’s Supper, leaving the Reformation permanently divided. He was ordained priest in 1506 and in his preaching he sought to communicate his political and religious ideals which were influenced by Humanism and his own study and interpretation of the Bible. Following the Humanists’ maxim, “Ad Fontes” (to the sources), he taught himself Greek and some Hebrew in order to be able to read the Bible and the Fathers. Zwingli memorized in Greek all of the Pauline Epistles having copied them down word for word. This spadework would later bear fruit in Zwingli’s powerful expository preaching and biblical exegesis. From 1506-1518 he was engaged in various pastoral duties. In 1518 he was elected “People’s Preacher” at the Great Minster Church (Grossmünster) in Zürich where he remained for the rest of his life. Over the portal of this church today one reads the following inscription: “Reformation of Huldrych Zwingli began here on January 1, 1519.” On this date the new pastor shocked his congregation by announcing his intention to dispense with the traditional lectionary. He said he will preach straight through the Bible, beginning with New Testament. In his preaching he also began to attack Catholic practices like purgatory, invocation of saints, and monasticism. Rupture with ecclesiastical authorities gradually followed, but his ideas met with strong support. He advocated the liberation of believers from the control of the Papacy and bishops. The sole basis of truth was the Gospel, and the authority of the Pope, the sacrifice of the Mass, the invocation of saints, times and seasons of fasting and clerical celibacy, etc. were rejected. The city council gave Zwingli its full support. The local bishop was alarmed but Zwingli challenged the Bishop for a public disputation, an “open warfare of the Holy Writ and by public meeting, following Scripture as your guide and master, and not human inventions.” At the first Zürich Disputation of 1523, the delegate of the Bishop, John Fabri was silenced and it was a decisive moment in evolution of the Zwinglian Reformation. He reorganized the cathedral chapter of Zürich in independence of Episcopal control. On April 2, 1524, Zwingli publicly celebrated his marriage with Anna Mayer. The Mass was suppressed at Zürich in 1525 and removal of images and pictures from churches followed. He instituted daily sessions of Bible reading and exegesis for preachers and laymen. Gradually Zwingli began to develop the most characteristic feature of “Zwinglianism”. He upheld a purely symbolic interpretation of the Eucharist. He published his views in a series of writings against Martin Luther. He maintained that it is only the communicant’s faith that makes Christ present in the Eucharist. There is no question of any physical presence. The Colloquy of Marburg in 1529 failed to reconcile the opposing parties and led to the first division in Protestantism. He had also other points of opposition to Luther like the distinction between Law and the Gospel. This point led him to affirm that Infant Baptism was a natural development from the Circumcision prescribed in the OT, as opposed to the Anabaptists who advocated only Adult Baptism. But the whole of Switzerland did not accept Zwingli’s teachings. As the movement spread to other parts of Switzerland, there began conflicts between those who accepted his teachings and those who rejected them. In one of those battles in 1531, Zwingli, who as chaplain carried the banner, was killed. This could have been avoided had he been less concerned to defend the gospel by means of the sword.

The Bible stood at the centre of the Zwinglian Reformation and together with it his radical new pattern of preaching straight from it. A second aspect of it was his stress on religion rather than ceremonial piety. Perhaps the heart of Zwingli’s religion could be summed up in one of his last admonitions: “Do something bold for God’s sake.”

Isaac Padinjarekuttu

(Professor of Church History at Oriens Theological College, Shillong)

Leave a Comment