Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav Kolkata event honours four Clergymen

Pope Francis asks businesses to support working women: They’re ‘afraid to get pregnant’

Study: Christianity may lose majority, plurality status in U.S. by 2070

Indian politician declines Magsaysay Award under party pressure

Like John Paul II, Pope Francis heads to Kazakhstan during time of war

Valson Thampu

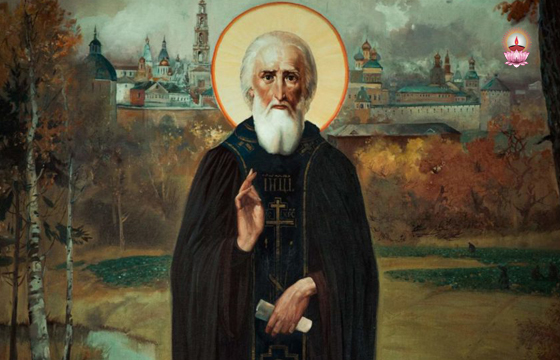

Fr Sergius haunts me these days. Don’t know him? Well, read Tolstoy’s novella of the same title. It will take you only a few hours. You can’t possibly invest your time better; especially these days. Why? Fr Sergius is Tolstoy’s acutely realistic anatomy of holiness. It will be a pity, if we remain blind to this portrayal of the pathos in the popular idea of holiness.

Fr Sergius was not always Sergius. He was, in his youth, a brilliant, keenly motivated army officer named Kasatsky. His ambition was to distinguish himself as the Emperor’s aide-de-camp. He fell in love with Mary, a suave, upper-class beauty. On the eve of their wedding, Mary confessed to him, somewhat casually, that she had a past. She was the Emperor’s mistress for a couple of years. It shattered the young man’s romantic idea of life and love. He resigned from the army. Gave away his share of the inheritance to his sister. Became a monk. Capt. Kasatsky became Fr Sergius. By the time Fr Sergius was forty years old, his reputation had spread all over Russia.

People say women have a strange, sexually-fizzy fascination for saints and priests. Women smouldering with resentment at the sexual crudity and emotional banality of their husbands are apt to believe that men in the holy cloth have some otherworldly charms. The verity of this make-believe apart, it did happen in Fr Sergius’ case that a rich widow – Makovkina, a lady with an easy conscience about morals-wagered with her friends on her ability to conquer the austere monk. She found her way into the cell of Fr Sergius late night, one day. What haunts the reader’s imagination is the way the monk deals with the temptation. As the woman moans her mock distress to lure the monk into physical proximity, the beleaguered monk readies himself for the moral battle to be waged.

“Yes, I will go to her, but like the Saint who laid one hand on the adulteress, and thrust his other into the brazier.” Finding no brazier there, Fr Sergius puts his finger over the flame of a lamp. It proves too much for him. He “writhed all over, jerked his hand away, and waved it in the air. ‘No, I can’t stand that!”

Not to be beaten, the monk takes the next step: more dramatic and precipitous. Even as the tempter whines and moans for him.

“Immediately!” he said, and taking up the axe with his right hand, he laid the forefinger of his left hand on the block, swung the axe and struck with it below the second joint. The finger flew off more lightly than a stick of similar thickness, and bounding up, turned over on the edge of the block and then fell to the floor” (Emphasis added).

His human weakness brought thus under control, Fr Sergius stands before the woman. “He hastily wrapped the stump in the skirt of his cassock, and pressing it to his hip went back into the room, and standing in front of the woman, lowered his eyes and asked in a low voice: ‘What do you want?’

She looked at his pale face and his quivering left cheek, and suddenly felt ashamed. She jumped up, seized her fur cloak, and throwing it around her shoulders wrapped up herself up in it.”

Most writers, save Tolstoy, would have ended the story at this high point. He chases the theme to its historical quarry. By now Fr Sergius is revered as a living saint. Miracles of healing are attributed to him. Yet, in Tolstoy’s ironic vision, this spiritual giant is portrayed as enfeebled by success and the miracles that happened on account of him. Tolstoy sharpens his irony by having Makovkina substituted in this temptation with a merchant’s daughter; young, physically attractive, but mentally retarded. The revered ascetic, despite his sinking physical powers, bursts like a bubble at the touch of a woman’s hands!

Why did the spiritual armour of the monk collapse utterly before a young girl? What does Tolstoy convey by giving his plot this shattering spin?

Tolstoy had a Kantian distrust of the miraculous. He treats the popular craving for miracles, and the willingness to indulge them, as a subset of power. Power corrupts. The more powerful a person becomes, the more apt he is to fall. As the tragedies of many a TV evangelist in recent memory tells us, the growing popularity and widening appeal of such people draw to them a greater degree of peril. The extent of the destruction this wreaks on these evangelical matinee idols depends on the measure of moral and spiritual enfeeblement that success, influence and affluence they command. In Tolstoy’s imagination, social and spiritual glamour are one and the same. The latter is, if anything, deadlier. It was as an antidote to the infections of glamour that Tolstoy did manual labour like a serf in his farm every day for five hours. He was clear that glamour, gold and power over others, comprise a peril nearly impossible to resist.

Tolstoy’s treatment of the austerity of Fr Sergius, for all its veneer of veneration, is ironic. It is not in the seclusion of a monastery, but in the rough and tough of life in the wider world, that a man’s spiritual mettle is strengthened and his character ribbed and reinforced. In comparison, a monastery is an artificial, sterile milieu. What is artificial weakens those who have recourse to it. The life of the ascetic, no matter how closely shut against the external world, is never free from its seductions. They come seeking him at unexpected hours, in situations of vulnerability. As a rule, we are overcome by what we deny. The history of India illustrates this.

He gained unrivalled authority over the people; besides their unreserved faith, of which the merchant’s decision to trust him with his daughter is an illustration. But, all that doesn’t mean that Fr Sergius had mastered the Kasatsky in him. In seeking refuge in a monastery from his personal tragedy, Kasatsky was escaping from himself, not dying out of who he was. Kasatsky assumed a new role; but didn’t become a new creation. The ambitious, romantically frustrated army officer, famished for power and splendour, continued to lurk in the backyard, not far from the façade of the iconic ascetic.

This insight is of immense contemporary relevance. It is unfair and inhuman to assume that, just because a young man decided to be a priest – or, a young woman, a nun – they have mastered themselves. On the other hand, as days go by, they inch closer and closer to the precipice. Insisting to the contrary is to take a naïve, infantile view of human nature; its intractable, subterranean currents and morbidities. The insight that Tolstoy adumbrates here is not unknown. Awareness regrading this exists; but the courage to face it and to address its raging implications is wanting.

Each passing day adds cyclonic power to the forces of nemesis forming itself over suppressed turbulence and forebodings. As Behadur Shah Zafar, the last Moghul ruler is reputed to have said, as the enemy was marching menacingly to his fortification, ‘It’s still a long way to Delhi!’

Leave a Comment